Tacumbu Prison

It was the Wednesday before Holy Thursday. In a little school in Caacupé, a reenactment of the Crucifixion was staged. The show was played by children dressed as Roman executioners and Jewish peasants. Gruesome, while at the same time inexplicable, it was a public school in a country where no religion will have official status. Or at least that is what the Constitution of Paraguay states.

The next day, we got up early to go to Tacumbú Prison. It is supposed that on a day like this, Jesus celebrated the traditional Jewish Seder of Pesaj, the holiday in which the liberation of the Hebrew people of Egypt is remembered. Through this, Christian churches recall the consecration of bread and wine in memory of Jesus and its distribution among the faithful. It is a celebration of freedom and social justice—something completely absent in Tacumbú.

I had never been in a prison. I confess that when I was invited to interview political prisoners in Tacumbú and write an article for a local newspaper, I felt a rush of adrenaline. What did I know about Tacumbú? That the Pibes Chorros had played there. That it is a damned and mythical jail, much like Carandirú in Brazil or Diyarbakir in Turkey. But unlike those, there is no successful novel or blockbuster film that portrays life there—all that I knew were the typical frivolities inherent to the conceptual structure of the privileged. The task of deconstruction never ends.

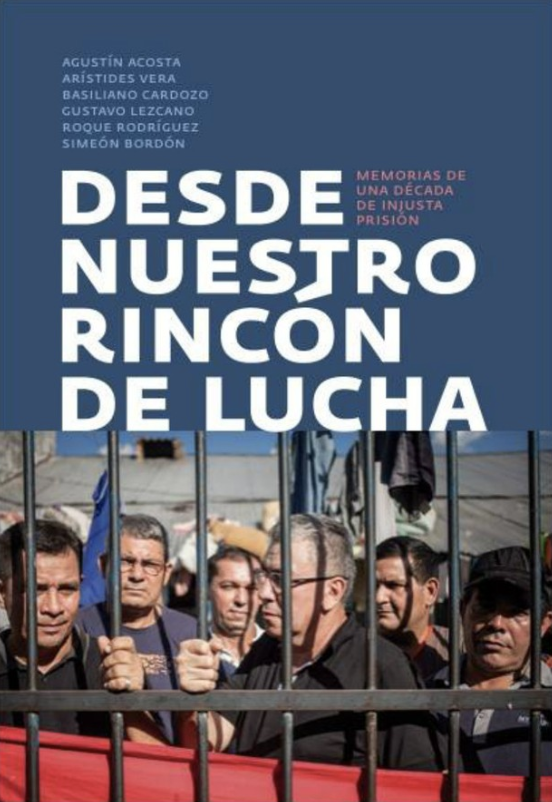

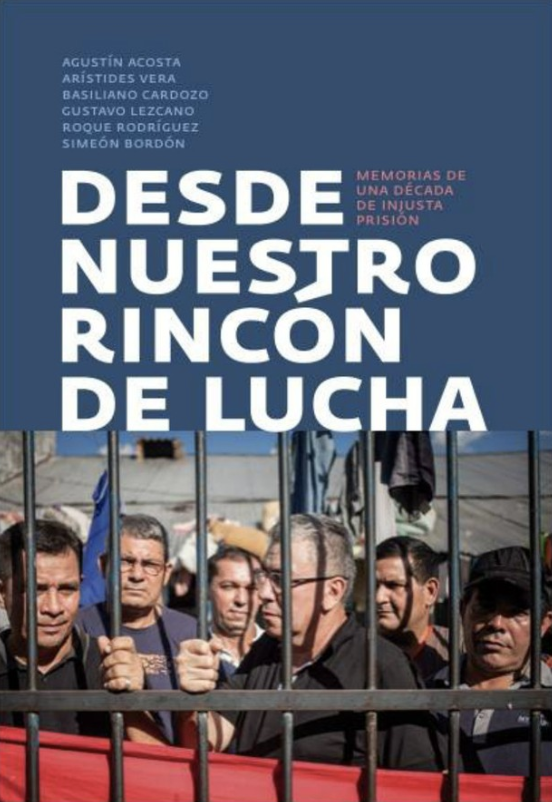

The quality of life will be promoted by the State through plans and policies that recognize conditioning factors, such as extreme poverty. We received previous instructions: wear long pants and shoes, just bring enough Guaranies for the bus ride home, keys and cell phones can be left at one of the little stands where the ladies are selling things out front, but you have to know which lady. Once inside, don’t walk with your eyes lowered, but don’t look anyone in the eyes either. Some friends of the organizations that worked with political prisoners were to wait for us at the entrance to take us to the pavilion of "The Six," the name for the peasant leaders condemned for the kidnapping and murder of Cecilia Cubas, the daughter of the former president of Paraguay. We were going to interview them.

The Nobel Peace Prize winner Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, the Argentine Association of Lawyers, the Argentine historian and writer Osvaldo Bayer; the cofounder of Madres de Plaza de Mayo Nora Cortiñas, the Lawyers Center for Human Rights, the Association of Lawyers and Lawyers of the Argentine Republic, the Center for Workers of Argentina, the Union of Lawyers of the State of São Paulo, and many other intellectuals, politicians, activists, workers, and organizations of Paraguay, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Mexico, and other countries were interested in the case of "The Six," demanding their freedom but not achieving favorable results.

Persons deprived of freedom will be held in appropriate facilities. From the outside, Tacumbú looks like a large, derelict bus terminal. The first thing that caught my attention was how low its walls were and how easy it would be to climb them. The prison is the center of a tight and chaotic urban network. There are small shops that offer food, clothing, guampas and thermoses for tereré, that family and friends take to prisoners during their visit.

In each corner, shacks made of planks and sheets house relatives of the inmates who decided to live as close as possible to them. The penalties of deprivation of freedom shall have as their object the readaptation of the condemned and the protection of society. The living conditions on either side of the Tacumbú walls do not differ much. On the one hand, there is a huge world of poor people who cannot cross the exit door. On the other side is a similarly large world of poor people who enter the prison on visiting days.

No one shall be deprived of freedom, or be subject to process, but mediating the causes and in the conditions established by this Constitution and the laws. Not only are there more than triple the inmates for the original capacity of the jail, but the vast majority of them are there without having been sentenced. I ask myself how often the poor outside will be condemned to enter, and when the poor inside will be able to leave, only to later reenter, each time with longer sentences. It is the oppressive spiral of those who have less.

Earlier that day, we were instructed to arrive later than planned because of the overabundance of visitors on Holy Thursday. We were greeted by members of the organizations that work with political prisoners. There were two endless separate rows, one for women and one for men, who took advantage of the holiday to come to Tacumbú. In the line of men there was resignation, and at times, in low voices, animated conversation. They wore Sunday clothes and some modest, dark suits.

Perhaps I could not fully appreciate the hardness of the faces of men or the injustice that was endured because I was accidentally submerged in the middle of their hardness and injustice that day. In front of us awaited countless mothers, old and tanned, hugging their tererés and Easter cakes, accompanied by daughters, nieces, and granddaughters, sisters-in-law, neighbors, and girlfriends of their kids that were deprived of their freedom. And children whose presence in that harrowing place made my skin crawl. Children who came to visit their parents or siblings or who were being taken care of by women who were unable to find a place to leave them on visiting day. What is the representation of the world for a child who must witness one of the most catastrophic prison systems on the planet? How is the disproportion justified between the crime committed—if there has actually been a crime—and the excessive punishment of sentencing someone to the most dangerous prison in Latin America?

Despite the presence of a dilapidated metal detector, apparently symbolic, the inspection process to enter the prison was manual: a stamp on my forearm, not unlike the one I got a couple of nights before at the entrance to a club in Asunción, and a crumpled little piece of paper, in exchange for my ID card. "Do not lose this. If you do, you will not be able to leave," the guards warned us. A thin and creased piece of paper, vibrant with waiting and anguish, so frail, this key to freedom. There was a brief discussion among the guards about whether I should remove my earring. The book in my hand did not present an issue.

We crossed a framework of metal bars and several pavilions, then corridors crowded with boys who did not have a place to sleep. We greeted "The Six" and finally settled into the cell of Aristides Vera, with Agustín Acosta, to begin with the important stuff, which was to discuss ideas. As if nothing of the monumental horror that surrounded us mattered. Even more: as if nothing existed but ideas and the future. They asked me if I spoke Guaraní. It gave me an inexplicable shame to say no. In deference to my condition as a foreigner, we kept the interview in Spanish. Vera and Acosta speak a polished Spanish; they speak like a teacher and a catechist, with a patient and pedagogical cadency. They not only told us about their struggle, but with their admirable composure they also taught us a lesson.

Throughout the years, I had the opportunity to listen to good teachers in classrooms, cafés, tribunes and jungles. The message of hope and social justice that I received in the overwhelming context of Tacumbú, completely detached from personal demands, was an opportunity to witness the human condition in the most revealing way. Only ideas matter. It is in homage to this teaching that we wrote, with as much fairness as possible, an article about the message we received and that we were invited to disseminate. To date, the article awaits publication.

Later that sad Thursday, back home, I watched on the news the staging of the Crucifixion in Caacupé. Year after year, in rural schools, children dressed as soldiers subdued peasant children. Jesus was crucified for only a few hours. The peasants, however, still await their redemption.

Ph: Yacare Volador

Ph: La Via Campesina

Ph Organización de Mujeres Campesinas e Indígenas Conamuri