Until the end of the world

In 1993 I travelled to Nepal with my friends Alejandro and Jorge. Alejandro recorded the trip with his VHS camera, and we edited the material in a very artisanal way. We shamelessly included music from Wim Wenders’s film Until the end of the world, since he is the absolute master of the road movies we wanted to base our lives on. There was no internet back then, no Instagram or YouTube either. We would get together in some friend’s house to eat empanadas, and somebody would bring a VCR and we would stay up talking all night long, completely amazed. Eventually VCR machines disappeared and the chronicle of this unbeatable journey became invisible.

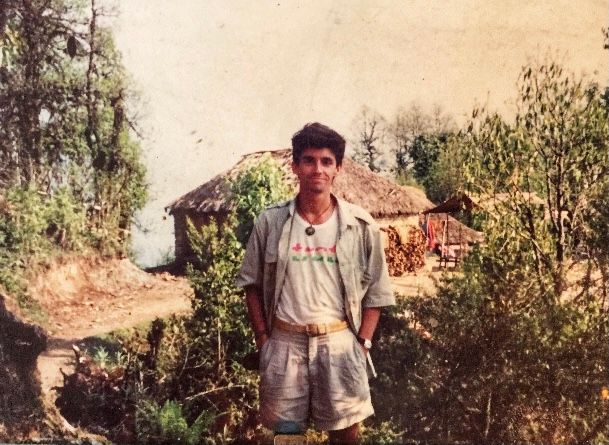

A few days ago Alejandro sent me the digitalized file from that trip to Nepal. I was very moved by the innocence of our youth and by the epic effort of going to the end of the world just because we though life could be wonderful. The original version of Until the end of the world is five hours long and our video of Nepal lasts over an hour, which shows how much more time we had thirty years ago. In tune with the attention deficit the proliferation of social media has thrown us into, I made a short clip - less than three minutes long - which tries to capture the intrepid spirit and the peak vitality of one of the happiest moments of my life.

(Castellano aquí)

In the beginning of the video, Jorge and I are at the old airport of Bangkok. We pass by the boarding gate of the Air India flight to Calcutta and we laugh, happy that our destination isn’t India. The weeks prior to the start of the video I had been in what was back then the Mecca of backpackers, Koh Phangan. It’s a dreamy little island in Thailand which, back then, didn’t have any electricity or postal service. The famous full moon parties that nowadays bring together international DJ’s, chartered flights full of Europeans and tons of cocaine, were in those nights an omelet of mushrooms, dances around bonfires and a Rastafarian playing guitar.

Part of our happiness stemmed precisely from not being in India. At some point in the eighties, the hippie rainbow that used to go from Katmandu to Goa had moved and the new gate of nirvana was Bangkok, with Kao San road, its legendary street of cheap pensions, ruffians and bars, and Koh Phangan, the island of freedom that inspired the novel The Beach and its film adaptation.

Three years before this journey, having just turned 25 years old, I had made my first trip to India in the hellish month of March 1990, when the Easter holidays along with a leave without pay allowed me to stretch the lousy two weeks of annual holidays capitalism offers its workers to a total of five weeks. When I was close to finishing my Law studies I had got an entry-level job in an important law firm in Buenos Aires. It was 1988, the economic debacle of Argentina was imminent and finding work was close to a miracle. I didn’t even have time to comprehend the brutal grinding corporate life would bring to my soul. The main incentive was that after a year of work I’d be able to save enough for a trip to India. The hyperinflation of 1989 delayed the dream a year longer.

Even though I’d had my decent share of backpacking around South America, nothing could have prepared me for what was waiting for me in India. I landed in Delhi surrounded by boiling heat and for ten rupees I got a bunk bed in the YMCA. Two days later I had a raging fever and an upset stomach, but even death would have been better than going back home. Delirious and vomiting, I read Forster’s Passage to India and wrote a poem on unrequited love. The boy sleeping in the bed next to mine gave me some Lomotil, dissolved in a glass of tap water with a purification tablet in it, and told me: “I think you’re going to die. You either go to Kathmandu or you go home. Make up your mind and I’ll drive you to the airport tomorrow”.

That was how I healed in Nepal, with its mountain-tempered climate and, more than anything, with the relief brought by the pizza and beer that thirty years of hippies had left as a present for the new generations that were beginning this millenary journey, which doesn’t have or need any explanation. In spite of how deeply transformative that first trip was, I didn’t have either the imagination or the audacity to think of a different destination than Buenos Aires and my alienating job. I needed to get a lot sicker before I could find the antidote.

From the day I got back to my parent's home, all I could think about was going back to the East so I could have more time to experience a life outside of the cannon, and to harden up enough so I wouldn’t die trying. I organized all my resources in order to do it. I got a better-paying job with longer holidays and I worked like a robot for the next eleven months. In the middle, I read Hesse, Maugham and Bouvier, the travels to the East of Pierre Loti and Flaubert; Jack London, Kerouac and Castaneda. This video is the registry of the last of those trips, which were the preparation of a slow but irreversible plan which led me to let go of it all and live a life of never-ending journeys. I’m still sheltered by it tonight, in the island of Timor, from where I’ll also leave in the morning.

That kid who walks around Nepal with his friends already knows his destiny. Nothing will be like he imagined, but he knows that time is conspiring in his favor. Despite the certainties I now have about my past, I still can’t believe I made it alive this far, and that I’m lucky enough to share it all.

Original VHS video: Alejandro